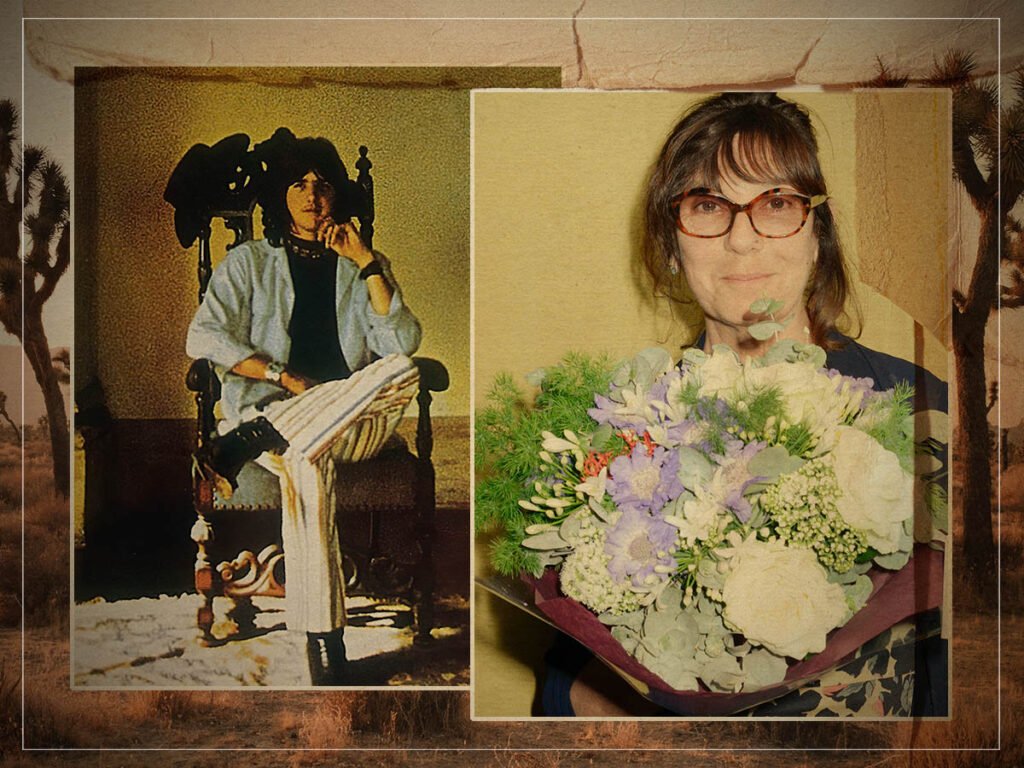

(Credits: Far Out / Brett Jordan / Pascal Ferro)

A hotel is a strange little universe: part refuge, part stage, and part confession booth. It is a space meant to be temporary, but sometimes it leaves a mark that’s more lasting than “home”.

In 1981, French artist Sophie Calle decided to test this idea by going undercover as a maid in a Venice hotel. For three weeks, she cleaned up after guests, but not in the way you think. Hidden in her mop bucket were a camera and a tape recorder. She photographed clothes slung across chairs, skimmed through unsent postcards, rummaged through toiletries, and even catalogued the rubbish. These black-and-white photos, which looked more like detective evidence than art, became The Hotel, a photo-text diary organised by room number. Later, it became both an art installation and a book.

What made Calle’s work so intriguing wasn’t just the voyeurism, though she’s been criticised plenty for crossing privacy lines with such abandon – it was the way she used absence to build presence. She was creating portraits of people not by showing them, but by showing the crumbs they left behind.

As The New Yorker’s Lili Owen Rowlands put it, “Calle is really looking for is more enigmatic and compelling than other people’s dirty laundry. Rather than erase the residue of human presence, as a ‘real’ maid is expected to, Calle does the opposite, preserving every stain and scrap as a sign or symbol.”

In this odd, brilliant exercise, Calle teased out the tension between what’s visible and what can’t be known. Even the most intimate details, a stained sheet, a love letter, a forgotten slipper, don’t necessarily bring us closer to understanding someone. They just invite endless speculation. Calle herself admitted she sometimes blurred fact and fiction (even staging one fake room in The Hotel) because, as she argued, what we wish to find shapes what we actually see.

“In this catalogue of objects, there is narrative tension, too—between those things that people pack to feel at home (framed photos, slippers, a hot-water bottle) and those they bring precisely because they aren’t (a brightly colored wig, a pair of platform mules, a bow tie).”

But hotels don’t just mirror our private selves; sometimes they become central characters in the stories of our lives, shaping legacies. One such hotel is the Joshua Tree Inn, an unassuming desert motel with a big musical legacy. The Eagles shot their 1972 debut album photos there, U2 named their fifth album The Joshua Tree, and artists like Robert Plant, Emmylou Harris, and Donovan have all played at the inn.

However, this unknown, lowly place became synonymous with the American rock legend Gram Parsons, the cult country-rock pioneer who helped invent “Cosmic American Music”, a fusion of country, blues, soul, folk, and rock that pushed past genre boundaries. Once a member of The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers, he famously inspired The Rolling Stones’ alt-country sound (think ‘Honky Tonk Women’ and ‘Sweet Virginia’) and worked closely with Emmylou Harris. But despite his enormous influence, real recognition didn’t come until after his posthumous 1974 album, Grievous Angel.

But why did Parsons keep returning to the Joshua Tree Inn? Because he craved an escape from the intense LA music scene, and Joshua Tree provided just that. But his story ended tragically. In 1973, Parsons checked into room number eight, where he overdosed on morphine and tequila. According to motel caretaker Margaret Fisher, a tall blonde woman showed up with a two-year-old child and “she brought everything with her. She brought the works”. Parsons died there, his life cut short at just 26.

Yet, the saga didn’t stop. Gram’s manager, Phil Kaufman, famously “borrowed” Parsons’ coffin at LAX, intercepting it before it could be flown to Louisiana. He drove it back to Joshua Tree National Park, took it to Gram’s beloved Cap Rock, and, fueled by beer and gasoline, attempted to cremate his friend’s body in the desert. The attempt failed, and Gram’s charred remains were eventually buried in Metairie, outside New Orleans.

For years, fans made pilgrimages to Cap Rock, visiting the spot where Parsons’ body was set alight. Recently, a piece of Cap Rock was moved to the courtyard of the Joshua Tree Inn, placed near the infamous room number eight. Today, a giant guitar monument sits there, covered with fan messages and offerings. Hardcore fans can even rent the room where the same mirror that hung on the wall when Gram died still hangs.

Hotels, it turns out, are not just places where we sleep or toss our suitcases for a few nights. They can become our most potent stage or canvas on which you can let your creative ideas come to life. Calle’s The Hotel shows how we reveal ourselves in the things we leave behind and carry, while the Joshua Tree Inn shows how some places hold onto our ghosts long after we’ve gone.

Related Topics