What does an artist see when they look in the mirror and paint? A window into the soul? A diary entry recording a moment in time? A self, or selves? The painter Lucy Jones has asked the question countless times, and always the answer is different.

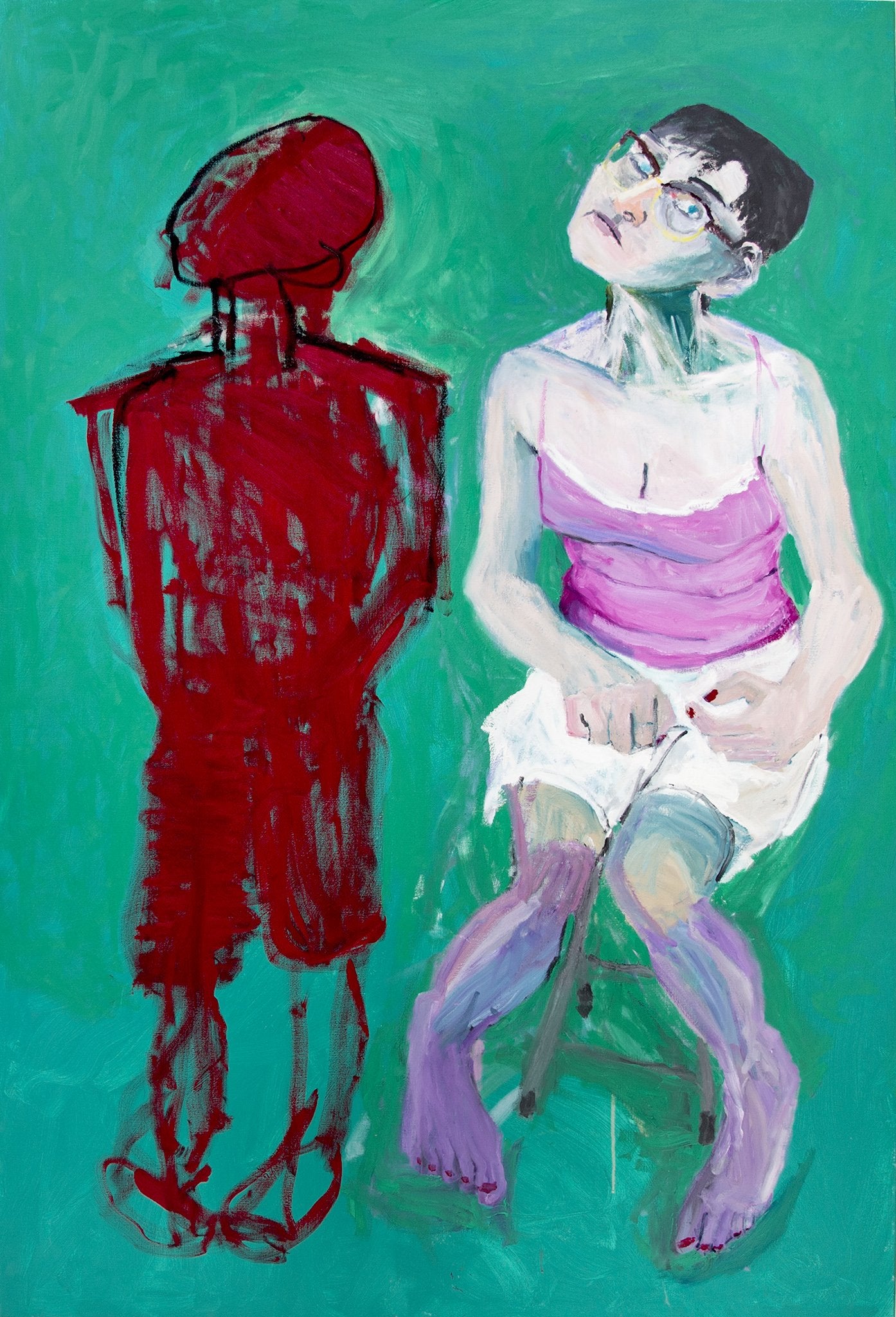

Take a self-portrait from 2013, when she was in her late fifties. She perches on a stool, knock-kneed, neck bent. Through glasses, bright blue eyes gaze interrogatively at the viewer. But what’s truly singular about the painting is the red shadow figure standing alongside the sitter. Its title asks a question: How Did You Get on This Canvas?

Cork Street in Mayfair, round the corner from the Royal Academy, is celebrating its hundredth anniversary as a hub for contemporary art. All the street’s galleries are in on the centenary, and the Flowers Gallery is using the occasion to celebrate the many self-portraits of an artist who had her first solo exhibition there in 1986.

The earliest painting on show in “totally, completely and absolutely Lucy Jones” is from a decade later. It shows her standing pigeon-toed with a paintbrush in her left hand and a walking stick in her right. Another, from 2000, shows the same walking stick detached from Jones, who is horizontally marooned at the top of the painting. The title: It’s a Long Way to the Bottom of This Canvas.

Jones has cerebral palsy. She’s 70 now. As a student, she initially struggled with the intense scrutiny required for self-portraiture. “I just didn’t want to look at myself in the mirror,” she says. “If you’re very depressed – I spent many years with depression – I think it’s really difficult to look at yourself.”

.jpg)

As she persevered, graduating from half-length to full-length images, it was as if she were describing her own relationship with her body, and her body’s relationship with the rest of us. “I suppose it was like coming out,” she says. “You can see a progression.” In Going Swimming, 1997, she posed in a swimsuit on a searingly yellow beach (Jones is a fabulous colourist). Being 50, 2005, went further. She and her husband had been in New York. “Peter took this picture of me looking out of a hotel window, of my backside. I thought, ‘Oh, I quite like my backside!’” The result was her first nude self-portrait, viewed from back and front, which she sees as “a continuation of who I am”.

In due course, she started to give her self-portraits titles. These ludic challenges feel very Lucy Jones. Who Is the Artist Round Here?; Remove Your Gaze. “I never used to have titles, because I didn’t want to direct people too much. The braver I got about talking about disability, it became easier. I’m quite often poking people in the ribs. It’s only after I’ve done them that I actually work out what they are. I look at it and then the title comes.”

The exception was With a Handicap Like Yours…, 2018, which shows Jones holding a handle for support while a disembodied third hand creeps onto the canvas. “A doctor said that to me. I thought, ‘Ah, OK, that’s a great title.’”

Eventually, text started to appear on her canvases, mostly in mirror writing. “I wanted to make it difficult for people to read it, because life is so…” she politely withholds an Anglo-Saxon adjective… “difficult.”

Jones works in a converted barn in a bucolic Shropshire village, 20 minutes’ drive from her home in Ludlow. I find her sitting in the studio on the first floor, where a blow heater is doing its best to spew out warmth (our meeting is on a chilly Sunday in March). The first and continuing impression is of a woman who is modest, but funny with it. What is it, I ask, that she thinks appeals to collectors of her work?

“It’s a very good question,” she says, “because I don’t know! In a way, I think they must be mad!” One thing of which she’s confident is that her success is not a product of her backstory. “I don’t think it’s particularly connected. When I first started out, I would never ever talk about my disability, because it was frowned upon and you would end up in a particular box. I don’t really want to be a poster girl. I’m quite private, and I want to say what I’m saying through the self-portraits.” Thus, from the Flowers exhibition, paintings like Blind Spot, 2012, in which a swipe of paint obscures her left eye. Or Unbalance: Tipping Point, 2022, which depicts Jones sitting on the floor but rotated through 90 degrees.

The backstory contains vast obstacles. “Now they call it neurodiverse, and it would be dealt with in very different ways, wouldn’t it? Sixty years ago it was all a bit desperate. But I could paint. It gave me something to base my life on.” She went to the progressive King Alfred School in Hampstead, and flirted with studying geography at Durham University. “But my sister pointed out that for somebody who can’t really walk, can’t really read and write, it could be tricky.” (A favourite word of hers.)

Jones progressed through a series of art schools – the Byam Shaw, Camberwell, the Royal College of Art – and found herself being taught by eminences: Leon Kossoff for a week, Frank Auerbach for a day. Word reached her that Auerbach liked her work. “It helps,” she says. “It boosts your confidence.”

Her education was rounded off by a placement at the British School in Rome, where a thrilling highlight was gaining close-up access to Michelangelo’s frescos in the Sistine Chapel when scaffolding was up for restoration. “These huge brushstrokes, and complementary colours that you couldn’t see before – violets and yellows – just incredible.” (In fact, the Italian artist who had the more profound effect on her was Giotto, for “the way he sets the figures in the landscape and paints them very sympathetically. They are really human.”)

Jones’s two years in Rome were “tricky”. At the time she was seeing a psychotherapist at the Tavistock, who “really didn’t want me to go without back-up. She fixed me up with somebody once a month. Difficult to say whether therapy really helped.”

When I first started out, I would never ever talk about my disability, because it was frowned upon and you would end up in a particular box

Two unrelated events caused the clouds to disperse. At 34, Jones was diagnosed with dyslexia. “That is incredibly difficult to say. It’s so totally embarrassing. I know people who always say, ‘Oh, dyslexia is a bonus.’ I’m thinking, ‘F*** you, it’s not a bonus. It’s s***.’” (Hence the challenge laid down by the backwards writing in her paintings.) Then, in 1986, she was exhibited at the Angela Flowers Gallery, as it was then known, and met her husband, “who changed my life. From there on my life has got better, really.”

She sees the self-portraits as an obverse to the townscapes she always painted in London – then, after the move to Shropshire, landscapes. “I needed two things. I need to look outwards and inwards.” Propped against the wall of her studio is a brooding depiction of conical, forest-skirted Clee Hill. For all such work in the outdoors, she draws in a kneeling position, which she can maintain for a couple of hours. “Then I have to move. I can stay out really quite a long time.”

She has also painted a series of portraits – of a pensive Grayson Perry, of Matthew Flowers “slightly averting his eyes as if there might be something more interesting going on behind”. A particularly touching portrait shows her father as an old man, pointing out of the canvas. It was painted in 2016, two months before he died. How did he and her mother respond to her career? “I think they were very very pleased and proud, but they found it very difficult to say that to me. I think it was so outside the scope that that was difficult.” Instead, she has two sisters and a brother who pay her the compliments their parents couldn’t.

Four years ago, in the depths of lockdown, Jones returned to herself as a nude subject. The standing figure she painted looks sternly but vulnerably over her shoulder. Her shadow is cast onto a door. She called it Being 66. “While I was doing it, I was thinking, ‘Nobody will see this picture, why am I doing it?’ Then, at the last minute, I put it in for the Ruth Borchard Self-Portrait Prize.”

Much to her surprise, she won. It felt like the reward for a lifelong project. “I think the self-portraits have been great. They have given me something completely different, and very personal, to study and concentrate on. I use the portrait to look out at you. Which I think I do quite well.”

‘Totally, completely, and absolutely Lucy Jones’ is on at Flowers Gallery, London, from 9 July until 2 August 2025