A Berlin-based artist who put up billboards advertising fake real estate projects in protest against runaway property development received more than 200 calls from would-be investors who didn’t get the joke.

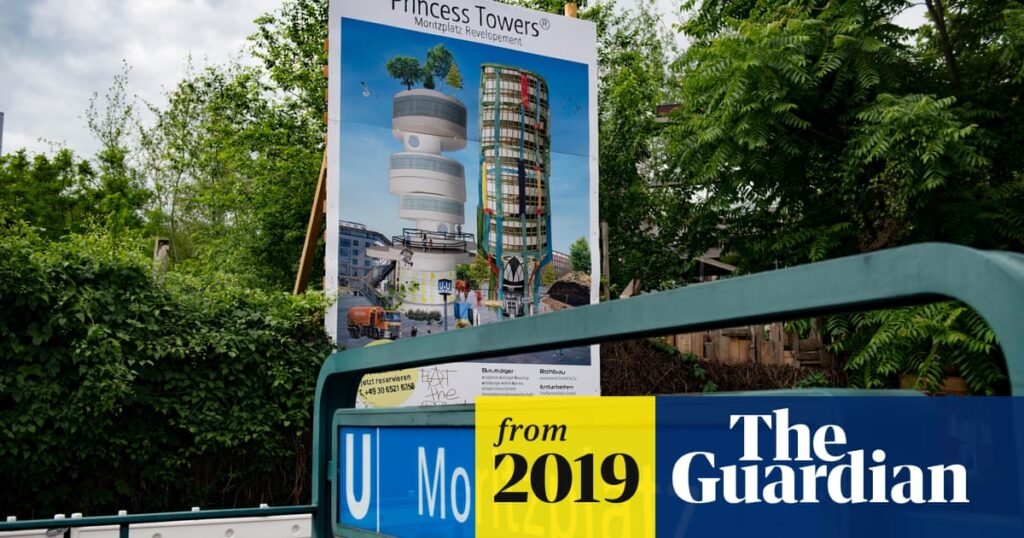

Three billboards appeared six weeks ago across Berlin advertising luxury new-build developments at in-demand locations. “Available 2021,” the billboards state. “No commission – reserve now.” They list a Berlin number to call.

At a distance, the adverts look plausible but closer inspection of the images visualising what the new properties would look like reveals odd details. Horses meander between buildings, road sweepers trundle incongruously across forecourts and fully-grown trees sprout out of roof terraces.

The small print provides a clearer clue to the reality. The project is led by engineers “Desperate Development” and real estate agents “Sharck Immo”, a word-play on the German miethai, or rental sharks, for slum landlords.

In a city where investors are scrambling to get a piece of the booming real estate market, the fake adverts have taken on a life of their own. Since they went up, Dorothea Nold, the visual artist behind the project, has been receiving up to six calls a day from interested buyers.

“All three developments have been very much in demand,” said Nold, 37. “Lots of callers were visiting Berlin but didn’t live here yet and were searching for something to buy.

“It seems some people only saw the phone number and blocked out the rest of the picture,” she added.

Most callers were Germans, but Nold also heard from would-be investors from as far away as Hong Kong and Australia, as well as Britain, Sweden and Norway. She said the response reflects the desperate scramble to invest in Berlin’s booming property market. Once a haven for artists and dropouts because of its exceptionally low rents, property prices rose by 20.5% in 2017, faster than any other city in the world.

“There’s a crazy amount of competition to buy apartments right now,” said Nold, adding that some frantic prospective buyers called three times in a row, fearing the units would be snapped up before they got a look in.

“Some people just seemed to want to get a piece of the action,” she said. “I was surprised how many callers just wanted to buy an apartment, regardless of the details. They said they’d take it, whatever it was.”

Nold, whose work explores the interplay of architecture and urban societies, intentionally put the placards in locations where, if they had been real, would have sparked the most outrage.

One stands outside Berlin’s biggest urban gardening project Prinzessinnengarten, which is currently fighting to secure a long-term land lease from city authorities.

A second can be found in a clubbing district in the city’s south east, and the third outside Künstlerhaus Bethanien, a former squat and long-time mecca for Berlin’s alternative arts scene.

With her work, Nold hopes to raise concerns about the ever-vanishing space in a cityscape once full of disused land but now quickly filling up with office and residential buildings.

“I put the placards in places in which I would hate to see developments,” Nold explained. “These are exactly the open spaces the city needs to preserve. I wanted to generate that shock moment when you see them and say, ‘oh no, not here as well?’”

But Nold hadn’t counted on the aggressive demand for new-build apartments in on-trend locations. Some callers were so enthusiastic about the idea of building over her favourite Berlin spaces that she told them the adverts were fake right away.

Then, unable to handle the sheer volume of calls, she began promising callers she would send further details by email. Nold plans to continue with interested buyers, sending them information on the prices and details of individual imaginary apartments.

She hopes that, when the investors take a closer look, the penny will drop. Meanwhile, the calls keep coming. The placards will be up for another month.