There is a particularly ugly nutwood carving of the infant Jesus dating from 1320. The nose is wider than it is long and the lower lip is pulled up, emphasising a ball-shaped chin and unpleasantly globular cheeks. Only a mother could believe this cherub beautiful, says Navid Kermani, who also takes issue with the three discoloured fingers Jesus is holding up, supposedly in blessing. “At first glance,” says Kermani, “he seems about to stick his bent brown fingers down your throat.”

Kermani, a German Muslim writer of Iranian Shia ancestry, has included this exhibit, which sits in Berlin’s Bode Museum, in his new book, Wonder Beyond Belief: On Christianity. A toxic little volume could have been written in which a Muslim writer visited European museums seeking out absurd Christian artworks for 40 or so vignettes. And then his publisher could have got the resulting lavish picture book out in time to cash in on the Christmas market. That is not what Wonder Beyond Belief is, though.

Instead, Kermani does something both refreshingly cheeky and philosophically instructive. As he wonders what Christian art says about Christianity, he meditates on works ranging from Old Masters (Leonardo, Caravaggio, Dürer) to the present day (Gerhard Richter’s stained-glass window recently installed in the great gothic cathedral of Cologne, with its colours randomly generated by computer).

Teasingly and sometimes caustically, his book teems with passages in which he looks with an outsider’s eye, wondering about the weirdness he sees. Did the Lazarus of Rembrandt’s painting really want Jesus to bring him back to life? Don’t Jesus and Mary, in El Greco’s Christ Taking Leave of His Mother, look like young lovers? Why do so many depictions of the crucifixion glorify pain?

Kermani baulks when I suggest he is a Muslim mocking Christianity. “I happen to be a Muslim,” says the 50-year-old. “But that’s not all I am, any more than a Christian is just a Christian or a Jew or a Jew. I’m not mocking anything.” So why write about Christian art? “It’s like when you fall in love. It’s beyond explanation – and that’s what happens whenever I write. I was in Rome for a year, on a fellowship, and was surrounded by Catholic art. That was the spur. That was when I fell in love.”

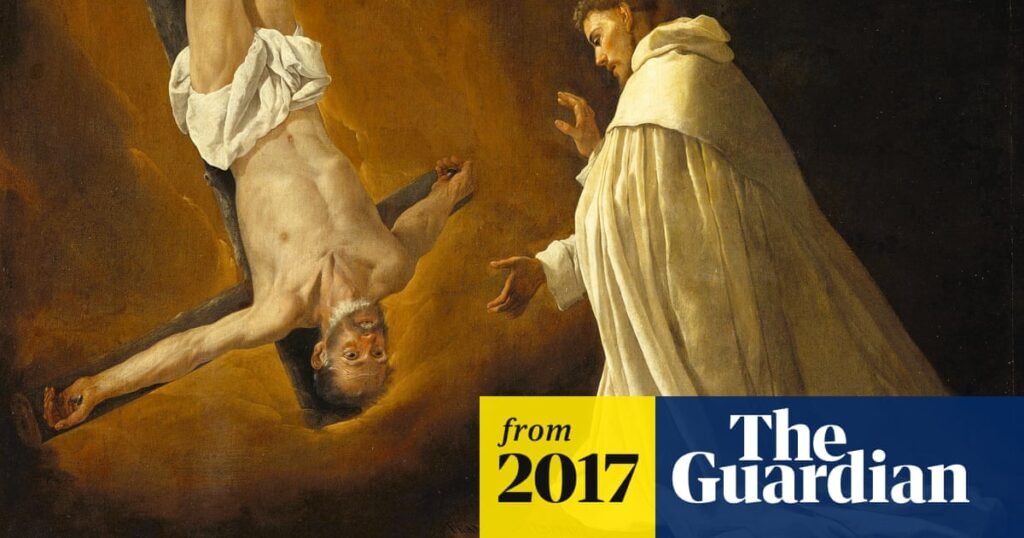

At the Prado in Madrid, he studies Zurbarán’s 1629 work The Apparition of the Apostle Peter to Saint Peter Nolasco. The apostle, the painting asks us to believe, has been hanging upside down on his cross for 1,200 years without dying and rotting, before being transported to appear before Nolasco, the 13th-century European saint.

Kermani is rather surprised at the apostle’s fate, the fact that he seems to be spending eternity inverted on a cross. “It is Hell, nothing less,” he writes, “Hell itself to which God has banned the apostle.” And if the apostle Peter is damned, what will be the fate of other people? And why, he asks, is Nolasco so indifferent to the apostle’s predicament? He seems more concerned about how it will play out on his CV, which may be rather shrewd. As Kermani points out: “He probably owes his canonisation as a saint to the apparition.”

Kermani’s bracing perspective is always steeped in learning. When he writes about the brown-fingered Christ child, he cites the Gospel of Saint Thomas to support his supposition that Jesus was not just the son of God but also a monstrous brat.

He has a particular problem with depictions of the crucifixion. “I grew up in a very Christian environment, in a small very Protestant German town,” says Kermani. “Although I really engaged with theology at school and university, and although maybe 500 people explained to me the significance of the crucifixion, I still didn’t get it. It revolted me.”

What about depictions of God? “No one has ever succeeded in painting a halfway believable picture of the Father,” writes Kermani focusing on the sub-Santa figure who looks down from some kind of window at Mary and Jesus, in Stefan Lochner’s 15th-century work Madonna of the Rose Bower. It’s an incendiary claim: perhaps even Michelangelo’s God creating Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is impious – reducing Him to a grandly bearded and implausibly buff airborne gent.

In the last vignette, Kermani controversially traces St Francis of Assisi’s barefoot mission of peace to Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil in Cairo during the Fifth Crusade. At that time, Kermani argues, Francis alone among Christians preached a kind of proto-interfaith dialogue, while others exhorted the faithful to slay infidels to secure direct access to Paradise.

Kermani’s book ends with a call to Islam to produce heroes of love like St Francis rather than testosterone-crazed jihadists. “I am frightened by everything I read in the papers about Islam,” he says. “Just this morning, then, news of another American hostage beheaded, of acid attacks on insufficiently veiled young women in Isfahan. But the time of the crusaders also produced a Francis and our time will also produce saints, God willing, with whom future Muslims will identify.”

Let’s hope so.