We’ve got Edvard Munch all wrong, said Nancy Durrant in The Times.

The common perception of the painter of “The Scream” is that he was an “angsty Nordic loner”, a tortured soul isolated from his fellow man. He certainly had his demons – mental health problems and alcoholism – but Munch (1863-1944) was also “a social animal”, with many friends who “cared deeply about him” and supported him at his lowest moments. We meet several of them over the course of this show, the first exhibition in Britain to focus solely on the Norwegian artist’s “prolific” output as a portraitist.

Bringing together more than 40 pictures, it follows Munch’s whole career, allowing us to observe how his style shifted over the years – from “the naturalism of his student days, seen in a contemplative image of his father”, to his experiments with symbolism, vivid colours and contrasts. There are “superb” portraits of the bohemians of Kristiania (Oslo), such as the “charismatic anarchist” Hans Jaeger, and of many of the city’s great and good. The paintings illustrate Munch’s “psychological acuity”, revealing him as a portraitist who strived “to capture his sitters’ true nature or state of mind, whether they liked it or not”.

Subscribe to The Week

The Week provides readers with a wide range of perspectives from 200 trusted news sources.

Try 6 Free Issues

Sign up for The Week’s Free Newsletters

From our daily WeekDay news briefing to an award-winning Food & Drink email, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our daily WeekDay news briefing to an award-winning Food & Drink email, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

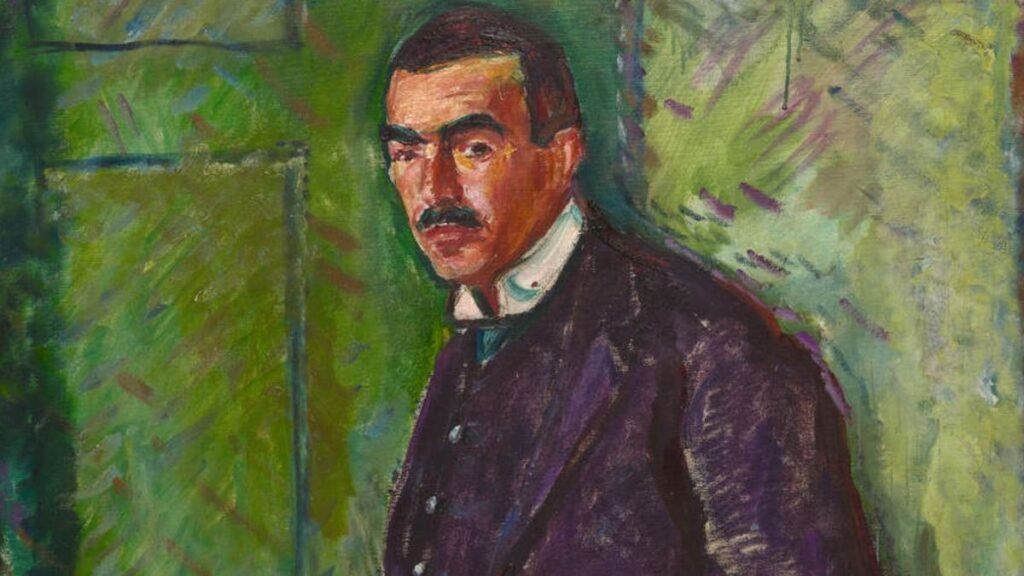

Few of Munch’s subjects cared for their portraits, said Jackie Wullschläger in the Financial Times. And small wonder: for all the “passionate eloquence and radiant colour” running through them, these pictures are far from flattering. Munch understood personality as “a battleground, created by conflicting desires and repressions”: and he pours these internal conflicts into his likenesses, making them appear “troubled” and “awkward”. A painting of the art critic Jappe Nilssen presents him as “a towering, glumly earnest figure in expensive purple”. Nilssen “hated it”, but it’s superb even so: “the longer you look, the more unnerving the picture becomes”, with “wild marks around the luxurious attire cohering into a menacing shadow”. Equally upset by his portrait was the playwright August Strindberg. So “appalled” was he by the “fierce gaze and demonic air” he’d been given, he asked the artist to try again. To no avail: the new version displeased Strindberg so much he threatened to kill him.

There are some “scintillating pictures” here, said Alastair Sooke in The Telegraph. Munch didn’t produce many portraits of women, but those that he did are great, notably the “fiery” double portrait of two sisters, which “is animated by a strong and uncanny doubling effect”. Yet for an artist known for his “vampiric femmes fatales and screaming ghouls beneath apocalyptic skies”, it all feels a little tame. There are too many routine portraits of “moustachioed men, dressed in sober suits” – too many waistcoats and watch chains, and not enough drama. Respectable as this show is, it’s “hard to get excited” about it.

National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, 020 7306 0055, npg.org.uk. Until 15 June