In a remote farmhouse on Hadrian’s Wall, something extraordinary unfolded during the 1970s. For over a decade, the internationally acclaimed artist Li Yuan-chia quietly transformed both the local and global art scene by founding the LYC Museum & Art Gallery.

Nestled in the rural village of Banks at the northern tip of the Pennines, the museum became a centre for creativity, inclusivity and community. Li’s revolutionary vision of art as a participatory and communal practice fostered a space where anyone – whether a renowned artist or a local child – could engage in the creative process.

Li Yuan-chia was born in 1929 in Guangxi, China. His early years were marked by displacement due to the Chinese Civil War, which led him to Taiwan at the age of 20. There, he became one of the founding members of the Ton Fan group, Taiwan’s first abstract art movement.

![Li Yuan-chia, Untitled, 1993. Hand coloured black and white print [Li Yuan-chi Foundation]](https://www.greatbritishlife.co.uk/resources/images/19295321/?type=mds-article-575)

The group challenged traditional Chinese painting by incorporating abstract expressionism, a radical departure from conservative Chinese artistic traditions that embraced Western modernist influences. Li’s art from this period displayed an affinity for simplicity, geometric abstraction and the interplay between negative and positive space.

His artist’s journey then took him to Italy, where he joined the Il Punto group, a movement that sought to integrate Eastern philosophy with post-war Western art.

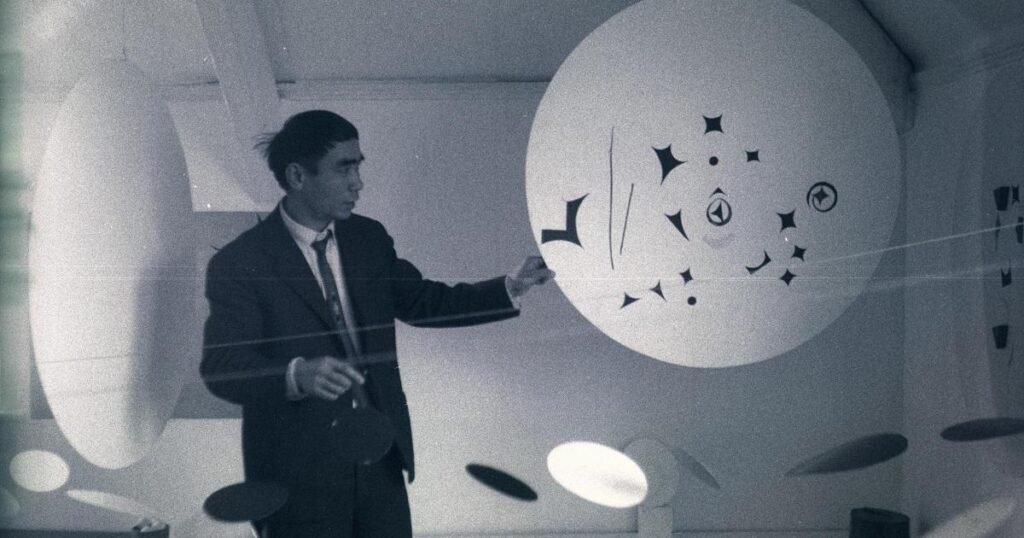

During this time, he developed his concept of the ‘cosmic point’, a symbol representing the beginning and end of everything, a recurring motif in his work. His exploration of minimalism and abstraction contributed significantly to his later artistic vision, where he sought to merge ancient Chinese philosophical ideas with contemporary art, believing that the smallest point of existence could contain infinite possibilities.

Li’s reputation as an artist grew and in the 1960s he relocated to London, exhibiting alongside avant-garde figures like Yoko Ono and Derek Jarman at the prestigious Lisson Gallery.

![Li Yuan-chia at the LYC Museum and Art Gallery, next to the window designed by David Nash [Li-Yuan-chia Archive]](https://www.greatbritishlife.co.uk/resources/images/19295322/?type=mds-article-575)

This participatory approach to art would become a hallmark of his later work at the LYC Museum. Yet, despite his success, he remained an outsider in the Western art world, struggling to secure financial stability in an often Eurocentric artistic landscape.

Li’s decision to settle in Cumbria in 1968 was a turning point in his life and career.

A fortuitous visit to his friend Nick Sawyer’s family home near Hadrian’s Wall in 1967 introduced him to the peaceful, rugged landscape of the North Pennines. Captivated by the area’s beauty and tranquillity, Li decided to make it his permanent home.

In 1971, he acquired a dilapidated farmhouse from Winifred Nicholson for £2,000, a transaction that marked the beginning of the LYC Museum & Art Gallery. This farmhouse, with its ancient history and rugged surroundings, became the foundation of one of the most unique and inclusive contemporary art spaces in the UK.

Winifred’s encouragement and support would prove vital to the success of the LYC Museum. Their friendship, based on a shared fascination with cosmic speculation and abstract forms, shaped the ethos of the museum, where both traditional and avant-garde practices could coexist, and Winifred encouraged Li to embrace his artistic vision.

Li envisioned the farmhouse as a centre for artists, a place where creativity and community could flourish. His notes from the time capture this dream: “I saw that it had a beautiful view, at the back of the house a garden can be made, at the front of the house a car park… the museum can help tourists and tell them the history of this district.”

He wrote to one artist: “The Newcastle bus (from the bus depot in English Street, Carlisle) leaves you at the level crossing in Low Row, and then it is a pleasant walk (if it is not raining) past Brow Top, High Birkhurst, Crookstown, Holmehead Farms, across the iron bridge, and up the hill past Banksfoot to LYC.”

One of those artists, Andy Goldsworthy, now an internationally renowned sculptor, had his first solo exhibition at the LYC in 1980. His land art, created in the local landscape around Hadrian’s Wall, reflected the museum’s blend of nature and abstraction.

Goldsworthy’s Hazel Stick Throws, Bank, Cumbria and How to Make a Black Hole were created at and for the LYC, embodying the sense of freedom and experimentation that Li fostered.

Nash’s sculptures, made from natural materials like twigs and branches, echoed Li’s own interest in blending organic elements with abstract forms.

Li invited hundreds of artists to spend time at Banks, offering them the opportunity to work or exhibit there and his support for artists extended beyond visual art, embracing experimental music and sound design.

One of the most notable figures to contribute to the museum’s creative atmosphere was Delia Derbyshire, a pioneering composer known for her innovative work in electronic music. Derbyshire, famous for creating the Doctor Who theme at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, moved to Cumbria after leaving the BBC in 1973.

The LYC’s exhibitions were not limited to famous artists. Local children’s work was displayed with the same care and attention as the pieces by international artists, and the museum regularly hosted workshops and performances that engaged the broader community.

Doll-making classes, rag-rug crafting, felt making workshops, poetry readings and experimental music performances were all part of the museum’s vibrant, eclectic programming. Dances were held at the museum too and Rafaele Appleby, granddaughter of Winifred Nicholson, fondly remembers a very wild ceilidh with the traditional Scottish Eightsome Reel being particularly popular.

The LYC Museum was unlike any other art institution at the time. Li’s philosophy was rooted in the idea that art should be a shared, participatory experience and the museum operated not just as a gallery, but as a living artwork – a space where artists, visitors and the local community could collaborate, create and interact.

![Li drinking tea with Winifred Nicholson, Cumbria 1975 [Demarco Archive]](https://www.greatbritishlife.co.uk/resources/images/19295332/?type=mds-article-575)

In the following years, there were exhibitions of Zambian crafts, an expo of the ten best living Chinese artists and shows by now internationally renowned artists like David Nash, Shelagh Wakely and Andy Goldsworthy. These exhibitions ran alongside displays about the fells, stone circles and weaving, while in another room, the LYC proudly exhibited work by local schoolchildren.

What made Li’s approach particularly groundbreaking was his commitment to what is now known as outreach and access. While a few museums at the time had basic friends’ schemes, educational and community programming were largely absent from most UK institutions. Li sought to break down barriers, making contemporary art accessible to all, regardless of age, background or artistic experience.

Ysanne Holt, who lived nearby as a teenager, recalls: “There was an air of informality, an atmosphere of play, of improvisation and experimentation with different forms and materials. It seemed like a place of possibilities, quite at odds with my teenage sense of everyday rural life in Cumbria.”

Nick Sawyer recalls: “It was important to Li that visitors felt free to explore different creative avenues. There were no strict rules at the LYC. It was a very liberated atmosphere, like when a young visitor to the children’s art space started painting over one of Li’s magnetic discs! The parents were quite distressed, but instead of a scowl, Li walked in with a smile on his face. He simply said, ‘You can paint wherever you want and on whatever surface you like in this museum’.”

Running the LYC was no easy task. At its peak, nearly 30,000 visitors a year came to the museum, with Li opening the doors seven days a week, often for long hours each day. He welcomed visitors personally, offering them a cup of tea, inviting them to explore the exhibitions and encouraging them to create their own artwork using the materials he provided.

Li was involved in every aspect of the museum’s operations, from curating exhibitions to renovating the buildings and producing publications for each show. He organised workshops, published an annual calendar for the museum’s growing list of ‘Friends’ and tirelessly raised funds to keep the space running.

The museum depended upon the support of local volunteers, friends and donors, many of whom contributed their time and resources to help Li realise his vision. His workload was relentless, and maintaining financial stability remained a constant struggle.

Before the LYC, modernism and the avant-garde seemed wholly alien to the fields and fells of North Cumbria. But the museum did not just change the landscape of Banks, it transformed the landscape of modern art, pioneering ideas of participation, accessibility, and inclusivity that remain deeply relevant today.

As Li once wrote: “LYC Museum is me. LYC Museum is all of you.” This simple yet profound statement captures the essence of his vision: that art is not a solitary endeavour but a shared experience, open to all.

Li’s legacy lives on, not only in the memories of those who experienced the magic of the LYC but also in the continuing evolution of the art world.

Li is buried at Lanercost Priory.

PHOTOGRAPHY SUPPLIED BY HELEN DICKMAN/KETTLE’S YARD

This is a version of an article that appeared in Cumbria Life in April. For a limited time, you can get six issues of the magazine for just £9.99. Visit our website at cumbrialife.co.uk, select any six issue subscription and enter the voucher code NEWS when prompted to redeem your discount.