In December 2021, FBI and IRS Criminal Investigation agents arrived on the posh Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, Florida, an island home to more than 60 billionaires, to raid a gallery called Danieli Fine Art. FBI agents stormed the premises, covered the windows with brown paper, and answered very few questions. As it turned out, the gallery’s owner, Daniel Elie Bouaziz, had sold an undercover agent what he said was a legit Jean-Michel Basquiat for $12 million. As an investigation would later reveal, it was actually a forgery Bouaziz bought for $495. He was sentenced to 27 months in federal prison by Judge Aileen Cannon—a Florida icon if there ever was one, if perhaps for the wrong reasons—and was locked up until October 2024.

Just a few months later, in decidedly less posh Orlando, the FBI was on hand to raid another emporium of paintings, this time the Orlando Museum of Art, which had just opened a massive blockbuster show of purportedly long-lost works by Basquiat, works said to have been found in a storage locker and forgotten about. Spoiler alert: The Feds deemed them fakes too, and the raid kicked off a long legal saga that I covered for this magazine in 2023, a tale that ended up being one of the most massive museum scandals in American history.

Last week, the FBI visited the Sunshine State once again. A man named Leslie Roberts was arrested in Coconut Grove, the boho-chic Miami suburb that’s long been an art-collecting hub nestled in the tropics, far from the gallery districts of New York and Los Angeles. Agents swarmed the Roberts-founded Miami Fine Art Gallery under the cover of darkness last Tuesday night and remained there until mid-morning Wednesday, perplexing locals restaurant owners and passersby. Helicopters hovered above, capturing b-roll for the nightly report.

The FBI was “doing its best to conceal its efforts, setting up tents so it can work and covering up windows with paper,” said reporter Liane Morejon, on WPLG Local 10.

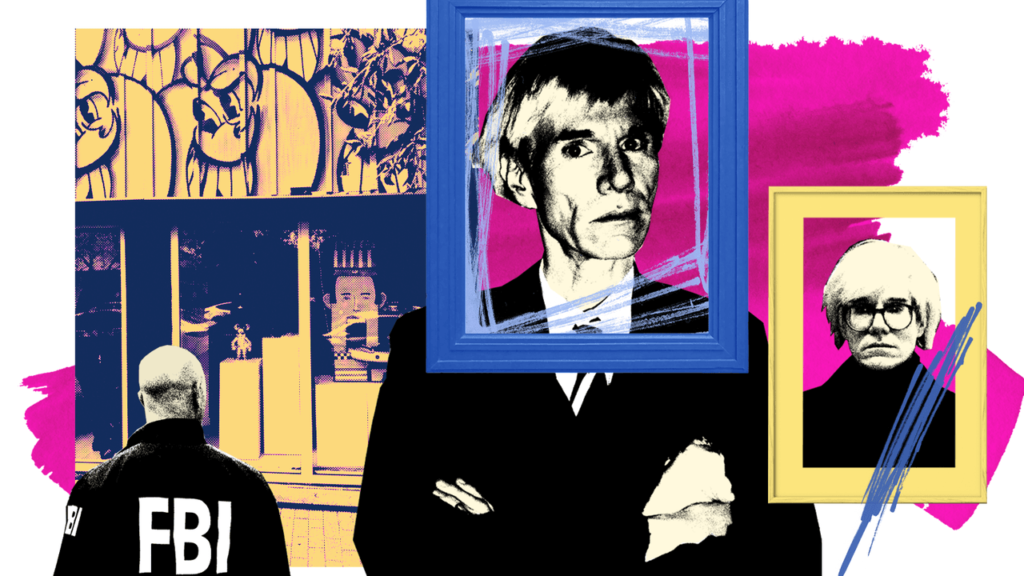

The Justice Department released the charges soon after: Roberts stands accused of wire fraud conspiracy and money laundering for selling fake works by Andy Warhol, and lying about their provenance. It wasn’t entirely a surprise; the criminal charges seem to stem from an earlier civil suit. Last year, Roberts was named in a civil suit filed by, among other parties, several members of the Perlman family, local art collectors who alleged that he had connected them to a fictitious representative of the Andy Warhol estate who sold them $6 million in works that turned out to be completely fake, and then refused to return the money. (“I don’t believe anything was a forgery—everything looked good to me,” Roberts told The New York Times last August in response to that suit, which is still ongoing after Roberts filed for bankruptcy and filed a petition for relief this month.) Now Roberts is facing up to 30 years in prison. Another man, Carlos Miguel Rodriguez Melendez, was indicted in the case for his alleged participation in the wire fraud conspiracy—according to the civil suit, Melendez allegedly arrived at the home of the Warhol collectors and pretended to be an employee of the auction house Phillips, trying to authenticate the works once the Perlmans started having their doubts. From there, the scheme quickly unraveled.

The general public has long had an obsession with art crime, whether it has to do with a heist at a museum where masterpieces by Rembrandt and Vermeer get lost forever, or market manipulation by shifty dealers that reinforce such notions that this whole art market thing is smoke and mirrors. But nothing gets people going like a good accusation of forgery, and in the last few years, a single state in the union has cornered the market in such tales.

But even by Florida standards, the narrative of Leslie Roberts is something beyond. Charging documents and previous legal filings paint a portrait of a man who has spent more than 15 years manufacturing identities for himself, opening galleries under increasingly absurd names, and getting entangled with the law over and over due to his inability to stop scamming unsuspecting art buyers with fake art. It was a family business—his wife, Silvia Castro Roberts, was in on it, as were their children, Leslie Roberts III and Brittany Lynn Roberts. And it all plays out in the inherently surface-level art scene in sparkly make-believe Miami, where you can will a Warhol into existence and find someone to trust that it’s real.

Miami gallerist Leslie Roberts is accused in a recently unsealed indictment of forging Warhols. Plaintiffs allege these artworks are fake Warhols making this the latest in a long tradition of alleged art frauds in Florida.From the Plaintiffs’ complaint.

The first thing you notice about Leslie Roberts are the eyebrows: two thick busy things, as demonstrated on his oddly captivating TikTok channel. He’s slight of build, reported to be five foot three when he was in his 20s. He’s gone through a series of names: now it’s Les Roberts, but it used to be Howard Roberts. And what’s the deal with his TikTok? It’s mostly just him in his apartment overlooking Brickell Key, lip syncing to songs, pretending to play guitar, with some FaceTune effects thrown in for good measure. He somehow has 566,000 followers. The last post went up March 27, days before the raid.

Roberts grew up in Perrine, Florida, a suburb of Miami, and his family was rocked early on by a shocking crime. His parents fought often, sometimes violently, and in October 1975, when he was 13, his mother shot his father in the head while he was sleeping, killing him. She was convicted of murder and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Roberts reportedly dropped out of the University of Miami after two semesters and worked at the local movie theater, where, according to The New York Times, he was fired for skimming cash off his customers. He found work at a penny stock outfit based in Denver, working out of the Miami office. At a certain point, he convinced his great-uncle, local concrete poohbah Frank Gory, to play the markets with him—Gory had sold his lucrative Gory Roof Tile Manufacturing Inc. a few years earlier, and handed over forkloads of cash to Roberts. The young trader parlayed a few bonanza trades into a gig at E.F. Hutton, where he quickly became one of the firm’s hottest stockbrokers and was lured to Merrill Lynch with a big contract. The only problem? His sales were fake, and the transaction sheets were printed on his home computer—at the end of the day he had falsified a reported $47 million in stock trading tips. In reality he was losing his great-uncle enormous sums on the way to a total loss of $9 million. He was arrested in February 1986, and by April 1987 he had pleaded guilty to three counts of mail fraud and conspiracy, and was and sentenced to 15 years in prison.