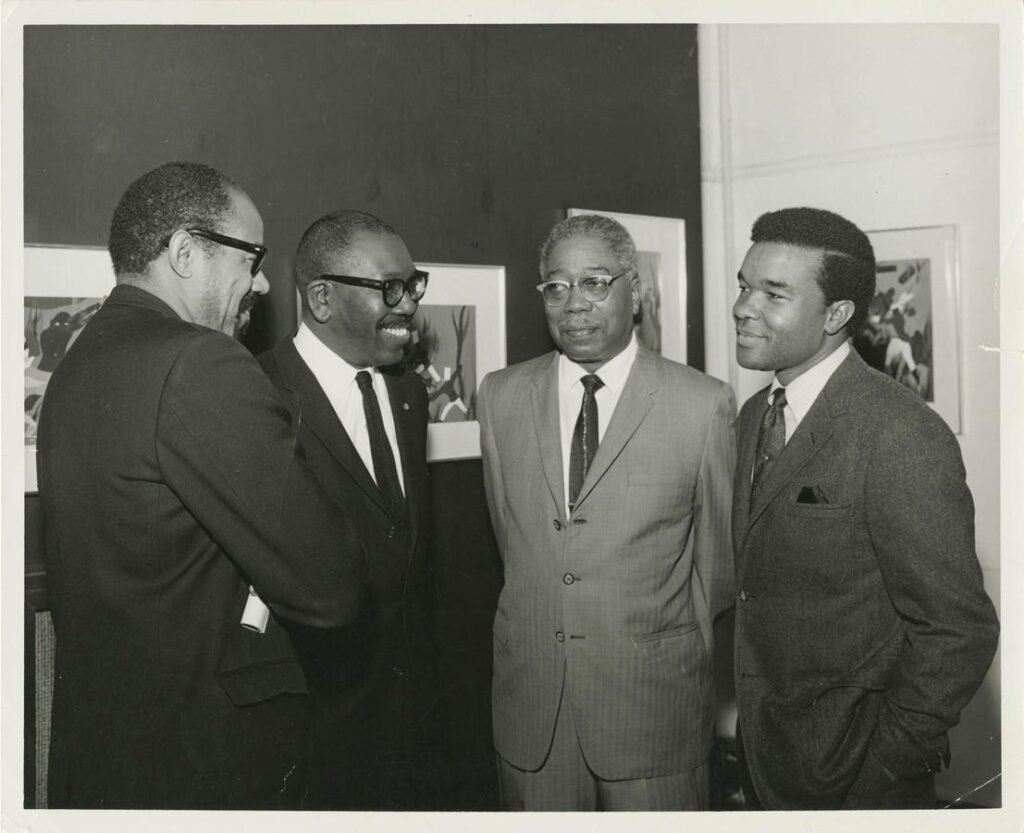

Walter Williams, Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and David C. Driskell at the opening of the exhibition at Fisk University in 1968 focusing on Lawrence’s Toussaint L’Ouverture series. Image courtesy of the David C. Driskell Papers at The David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland, College Park. Gift of Prof. and Mrs. David C. Driskell.

Image courtesy of the David C. Driskell Papers at The David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland, College Park.

The thesis is simple, surprising, and undeniable: Nashville as central to African American fine art in the 20th century.

Central to its cultivation, production, and promotion. Central to the genre-defining artists and exhibitions popularly associated with Harlem, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles–the consensus meccas of 20th century Black art.

Fisk University is the reason why.

The oldest institution of higher learning in Nashville. Historically Black.

Harlem Renaissance icon Aaron Douglass–painter of the famed Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture “Aspects of Negro Life” (1934) murals in Harlem–founded Fisk’s art department in the 1930s. He was first invited there by Charles Spurgeon Johnson (1893–1956), architect of the Harlem Renaissance, founder of “Opportunity Magazine.” They knew each other in New York.

Johnson started working at Fisk in 1928 and in 1946 would become the school’s first African American president. Douglass was initially brought down in 1930 for a mural project, then began teaching part time before launching and leading the department.

Arna Bontemps (1902–1973) worked in the library. Another pivotal figure in the Harlem Renaissance, the author, poet, researcher, and archivist relocated to Nashville in 1943, serving as a librarian and professor at Fisk until his retirement in 1965.

In 1966, Douglass handed the art department over to David C. Driskell (1931–2020). Driskell, who came from Howard University in D.C., is notable for his artwork; he is legendary for his curation and historical research into Black art in America.

In 1976, Driskell produced the most important showcase of African American fine art before or since. “Two Centuries of Black American Art” was foundational for the field of African American art history. Driskell put the show together while working at Fisk.

Washingtonian Alma Thomas’ (1891–1978) history-making 1971 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York–the first African American female artist to receive a solo show there–mimicked a similar presentation produced previously by Driskell at Fisk.

Driskell showed New Yorker Jacob Lawrence’s (1917–2000) Toussaint L’Ouverture series at Fisk in 1968. One more in a staggering sequence of presentations highlighting the best of the best in Black art.

Driskell’s good friend William T. Williams (b. 1942), one of the foremost abstract painters of the past century, New Yorker, was an artist in residence at Fisk in 1975. Famed Chicago photographer and filmmaker Robert “Bobby” Sengstacke (1943–2017) was an artist in residence and taught classes there in 1969.

Nashville’s central role in the story of African American art in the 20th century is laid out in full for the first time during a pair of exhibitions, “David C. Driskell & Friends: Creativity, Collaboration, and Friendship,” at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, and “Kindred Spirits: Intergenerational Forms of Expression, 1966–1999,” shared between the Frist and Fisk University two miles away.

“People have been blown away to know how many artists came to Nashville and did exhibitions here like Alma Thomas,” Frist associate curator Michael Ewing, a Fisk University graduate, told Forbes.com. “A student right now, there’s work by Alma Thomas that hangs on the campus of Fisk University, work (by her) just got into the White House during the Obama term. Fisk just did an exhibition in partnership with Denise Murrell, the Harlem Renaissance show (at the Metropolitan Museum of Art).”

“David C. Driskell & Friends” highlights Driskell’s artistic legacy and the importance of his relationships with fellow artists—many of whom hold a significant place in the 20th century art canon, such as Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Lawrence, Thomas, Kara Walker, and Hale Woodruff. In total, more than 70 artworks by 35 prominent African American artists, as well as ephemera from the Driskell Papers, exemplify the artists’ unique friendships.

“When you’re seeing this ‘Driskell and Friends’ show, none of these artists are strangers to Nashville,” Ewing said. “All of these artists are here.”

A fantastic photograph, blown up wall size and on view at the Frist, shows artist Walter Williams, Lawrence, Driskell, and Douglass side by side during the opening of Lawrence’s Toussaint L’Ouverture show.

“When you think about museums, we talk about these amazing African American artists, but sometimes these very artists at these times weren’t able to actually go to their openings,” Ewing reminds.

Don’t forget, Driskell arrives in Nashville in 1966, only two years following passage of the Civil Rights Act and the abolition of Jim Crow segregation. For all its race problems, and it had numerous, Nashville was a generally more progressive city than what was found elsewhere around the South.

Fisk housed Nashville’s first art museum, and white residents were welcome to view the artworks and exhibitions on view same as African Americans.

David C. Driskell Comes To Nashville

David C. Driskell. Mask Series II, 2019. Relief woodcut; 14 1/2 x 11 in. The David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland, College Park. Gift of Raven Fine Art Editions, 2019.10.002

David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland, College Park.

Driskell was 36 and working for his mentor James A. Porter as interim chair in the art department at Howard University before taking the job at Fisk. Douglass fist invited Driskell to campus as a speaker at the school’s renowned Spring Arts Festival.

“The year that Driskell comes he sees Sydney Portier and Nina Simone, so he’s like, ‘Man, it’s happening, something really interesting is happening here,” Ewing explained.

The legendary Douglass was connected to almost every important Black cultural figure in America at the time and invited them to visit.

“He’s getting letters–one of the artists we’re championing in the (‘Kindred Spirits’) show, Lifran Fort, she graduates in 1966, she talked about in class when people would pass the mail to Aaron Douglass, there would be a letter from Langston Hughes. Zora Neale Hurston spent some time and came to Nashville. So many people are coming here,” Ewing said.

As much as Douglass invited Driskell to speak, his ulterior motive was recruiting Driskell to take his place. The pitch was successful.

“(Fisk) gave (Driskell) the capacity and space to build,” Ewing explained of Driskell’s decision to move from D.C. to Nashville. “He’s coming from Howard and when you work at your alma mater, he already reached a certain capacity. He thought, ‘What more could I bring to Howard? All of my heroes are there.’ What Nashville gave him was the possibility, the capacity to dream and to explore, and as a young curator and artist, the space to reimagine that landscape.”

More practical considerations also factored into his decision.

“When Driskell comes to campus, he’s one of the highest paid professors, even over scientists, he was one of the highest paid people. Period,” Ewing said. “That’s how much they wanted Driskell. That was one of the things that Aaron Douglas told him. Driskell says Aaron Douglas (told him) whatever you want, ask for it.”

In addition to the handsome salary, Driskell asked for a building all his own for the art department. He asked for more full-time staff. He wanted funding for visiting artist and artist-in-residence programs. He got it all.

Professional freedom and autonomy and support. Driskell could go nuts. Chase his wildest curatorial fantasies. Hire the best people.

“He’s at a point where he really wants to make an impact and start to curate and produce the shows that he’s been dreaming about; Fisk is that opportunity,” Ewing said.

Born and raised in the South, Tennessee’s lingering racial tensions didn’t scare him the way they might have outsiders. 1966 was Fisk’s centennial year. Douglass was passing the torch to a new era of Black leadership. Driskell’s tenure at Fisk, 1966–1976, bridged a similar passing of the torch in the Civil Rights movement from the MLK, “we shall overcome” era, to a more militant, Black Power era. Coincidentally enough, one of the essential figures in that latter era, Stokely Carmichael, was a student of Driskell’s at Howard.

The times called for new perspectives. Douglass knew it and Driskell had them.

Earl J. Hooks

Walter Henry Williams, Jr. ‘Roots,’ 1975–77. Oil and mixed media on wood board; 47 3/4 x 60 7/8 in. Courtesy of Fisk University Galleries, Nashville, TN, 1991.2211.

Jerry Atnip

Indispensable to Driskell’s success at Fisk–his right-hand man–and more broadly to the success of Fisk’s art department in the later third of the 20th century, was Earl J. Hooks. Hooks was a first-rate artist in his own right as a photographer and ceramicist. He came to Fisk in 1968.

“Kindred Spirits: Intergenerational Forms of Expression, 1966-1999” explores the legacy and influence of Fisk’s art department with Hooks as the central figure. The chosen timeframe encompasses Driskell’s arrival at Fisk through Hooks’ departure after more than 30 years teaching. The span is also significant for predating the Frist Art Museum which wasn’t founded until 2001.

Both shows and the featured artists also serve as love letters to Historically Black Colleges and Universities for their defining role in shaping African American art.

“You have John Biggers who starts the art department at Texas Southern. You have people like Charles White who’s at Hampton University,” Ewing explained. “Hale Woodruff, a lot of people don’t know he graduated from Pearl High School in Nashville, but also what he does in Atlanta. Aaron Douglas, of course, who starts the department (at Fisk).”

Woodruff (1900–1980) served as art director at Atlanta University and taught classes in Atlanta at Morehouse and Spelman colleges as well. Bobby Sengstacke was a Bethune Cookman grad. Thomas was Howard University’s first fine arts graduate in 1924. Catlett later attended Howard.

HBCU’s continue producing the finest minds in Black art.

“When this show ends, I’ll be 36. As a curator, I’m now the same age that David Driskell was when he first came to Nashville in my role,” Ewing said. “For my first show ever at the Frist to be ‘David Driskell and Friends,’ and then to create ‘Kindred Spirits,’ and partner with my alma mater, it allowed me to start by honoring my ancestors and the elders within the art space.”