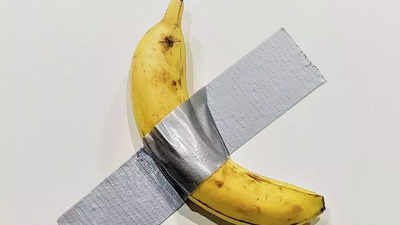

When visitors to a museum in Seoul saw a banana duct-taped to the wall last year, they probably had very contrasting reactions. The arterati must have exclaimed at how Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan was pushing the boundaries of conceptual art, while some would have shaken their heads at what passes for art these days. One hungry viewer went a step further and polished off the banana, leaving the peel still taped to the wall.And this was no ordinary banana. Though the artist had purchased the fruit at a local market, a version of the piece sold a few years ago for $120,000 in Miami. So, when is a banana just a banana and when does it turn into art?

Like beauty, it’s all in the eye of the beholder or your wealth manager, as the Financial Times noted in a recent report pointing out how a growing number of them now offer art services. In India, too, art has been growing as an asset class, and the slump of 2008-2009 is now a distant memory. In September, Amrita Sher-Gil’s 1937 canvas, The Story Teller, fetched Rs 61.8 crore, making her the priciest Indian artist. According to the ‘State of the Indian Art Market Report FY23’, there was a 9% rise in turnover and a 6% rise in the number of works sold from the previous year, making FY23 the most successful year for Indian art at auction. “Art has always been a lucrative investment among high-net-worth individuals (HNIs) for diversifying wealth and creating value. Today, the pool of investors looking to include fine art in their investment strategies is widening,” noted Pallavi Bhakru of Grant Thornton Bharat which brought out the report.

Besides financial motivations, there is also the social status that comes from hanging a Husain on your wall. How else can you declare that you have both taste and bank balance?

MARX & THE MARKET

But where would you say the value of art comes from? Is it anything that an artist/critic declares is art, and can anyone turn a urinal into an object worthy of a spot in the museum like Marcel Duchamps did? The answer is complicated. Asked whether value comes from labour, as Marx said, British artist Grayson Perry conceded that the man hours count but still don’t account for the crazy prices of some pieces of art. “It’s fascinating, the idea of value in the art world, because at a certain point, it goes stratospheric and it’s ridiculous. It’s pure market economics, and value is what somebody will pay for it.”

Even works that don’t seem conventionally “saleable” can catch the eye of an eclectic collector. Some years ago, collector Anupam Poddar, who snapped up the works of many rising artists before they became marquee names, narrated the story of how he had brought home a cow-dung work by a then not-so-famous Subodh Gupta to his family’s horror. The household then had to deal with an Anita Dube sculpture made from human bones in the dining room.

BLUE-CHIP MODERNS

Not everyone is as adventurous in their art tastes. While young contemporary artists create edgy, exciting and provocative work at biennales and art festivals, galleries still have to deal with buyers who want to match the painting to the sofa and shy away from work that’s either too bold or grim. In the auction market, it’s the ‘blue chip’ artists who rule the roost. Buying a modern master such as VS Gaitonde, SH Raza, MF Husain and Amrita Sher-Gil is like buying an established brand. It comes at a price, of course, since supply is limited. Vasudeo Gaitonde is a consistent record-breaker at auctions because he wasn’t very prolific in his lifetime. The few collectors who do own Gaitondes are often unwilling to part with them.

Contemporary art, on the other hand, is more speculative since it is not clear which artists will pan out over time. Plus, the art market is far more opaque than the stock market. There are no P/E (price to earning) ratios that one can look up, and pricing isn’t transparent. That’s why homework is important. For instance, a serious buyer could research the price of similar works of the same size and period to find out if they are getting a good price. If the artist has other works in private collections or has been featured in big international shows, it shows that there is some depth to his or her body of work. Then there is the all-important provenance which ideally should trace back to the artist.

Kito de Boer, one half of the famous Dutch collector couple who came to India to set up the McKinsey office in 1993, says he and his wife Jane spent a lot of time meeting artists, gallerists and collectors, and drinking a lot of chai and whiskey. “There is a rule in becoming ‘expert’ called the 10,000-hour rule. It basically says that you need to spend a lot of time to become an expert. This is true in art – your eyes need to see a 1,000 works to begin to become an expert. At the start of the journey- before you have seen the 1000, you have to meet those who have. You don’t have to agree — you have to discover your own voice — but you have to listen and understand.”

And even if you end up not buying anything, it’s worth the effort.

PS: Still curious about the banana? Nope, it’s not about male sexuality (though it’s fine if that was your takeaway). It was the artist’s way of poking fun at the art world and its pretensions