****

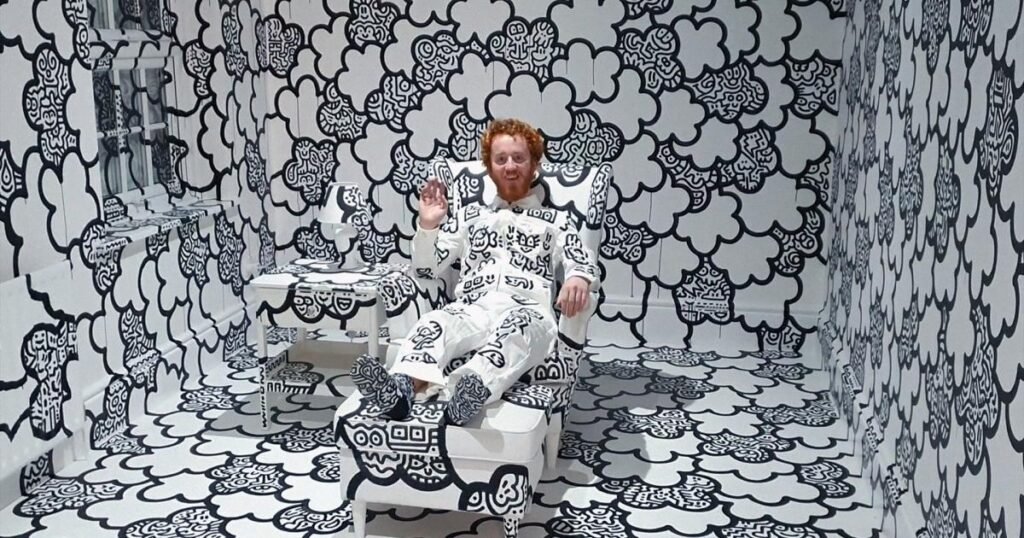

THE man who bought a big house, painted it white, then doodled over everything. Walls. Floors. Ceiling. Duvet cover. Toaster. Everything.

It sounds like one of the odder items from BBC Breakfast or, heaven help us, The One Show. The story of Sam Cox, aka Mr Doodle, did indeed attract attention around the world. Here was a real-life English eccentric and successful artist.

What viewers did not know was that Cox was being driven mad by his alter ego and had been for some time.

This extraordinary film by directing trio Jaimie D’Cruz (Exit Through the Gift Shop), Ed Perkins and Alex Nott tells the disturbing story of what happened when obsession met opportunity and raced out of control.

The Trouble with Mr Doodle opened when the white house was ready for the first stroke of the artist’s pen and looped back from there to his childhood. “It did cross my mind there was something different about him,” said his mum of the red-headed boy who would spend 15 hours a day drawing.

It was clear from interviews with his parents, friends and art teacher that this was the beginning of a cautionary tale. Yet on the surface all was well. Thriving even. Sam was an online hit, commissions were coming in, there were trips to Japan. Best of all he met Alena, a fellow gentle soul from Ukraine. The boy bullied at school was winning at life.

Read more

The trouble, to quote the title, was Mr Doodle. Where Sam was shy, awkward and reclusive, Mr Doodle was a shouty street artist brimming with confidence. The invented character “took over” and the doodling became increasingly manic. Sam’s mother used the word “possessed” reluctantly, but that is how it must have seemed. At one point he called her Nigel Farage and believed Donald Trump had asked him to doodle on the US/Mexico border wall.

Other filmmakers might have brought on a mental health professional to explain what was happening. Instead it was left to the film’s other trio, mum, dad and girlfriend, to describe what it felt like to watch, powerless, as illness took hold.

Further helping our understanding were illustrations and animated sequences of such high quality, one fancied Mr Doodle himself would have approved of them. Together, the artwork and the family’s recollections were as clear a guide to a major breakdown as it is possible to get at one remove.

Recovery was slow, with setbacks along the way. Occasionally, the film’s two-hour running time made itself felt. At other points, particularly the final section, the pace felt rushed. I would have liked to know more about the treatment he received and how he was doing today. How common, or not, was his experience?

As his mother acknowledged, they were lucky to get their Sam back. This was a story with a positive ending. Other families watching won’t have been so fortunate, but anything that aids our understanding of mental illness, as this remarkable film surely will, is to be welcomed.